Spoiler Alert. You’ve been warned.

And now things are already being transformed

PROMETHEUS BOUND [1329 / 1080], Aeschylus (trans. Ian Johnston)

from words to deeds—the earth is shuddering,

the roaring thunder from beneath the sea

is rumbling past me, while bolts of lightning

flash their twisting fire, whirlwinds toss the dust,

and blasting winds rush out to launch a war

of howling storms, one against another.

The sky is now confounded with the sea.

This turmoil is quite clearly aimed at me

and comes from Zeus to make me feel afraid.

O sacred mother Earth and heavenly Sky,

who rolls around the light that all things share,

you see these unjust wrongs I must endure!

Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin did the hard work for me in parallelizing myth and Oppenheimer in American Prometheus, just around the time Christopher Nolan was debuting an origin story of his own: Batman Begins.

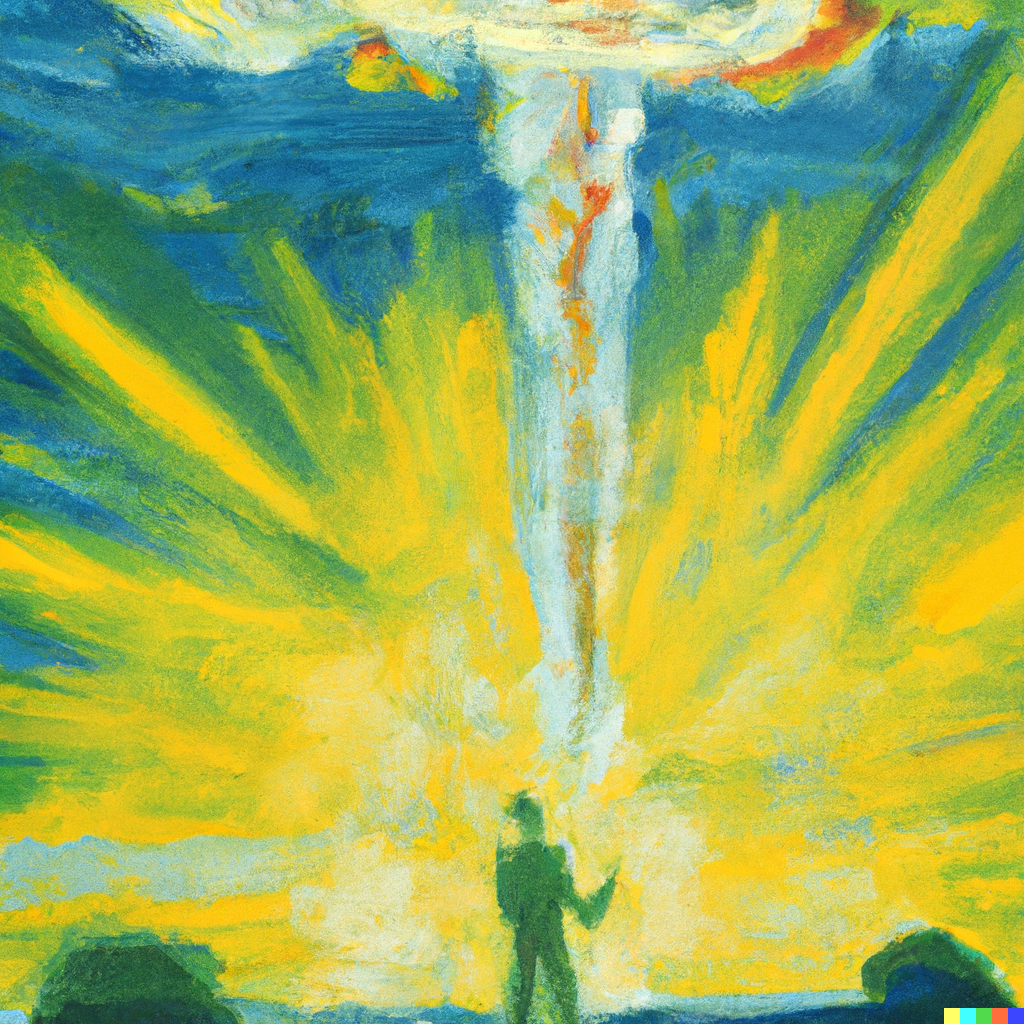

To experience Oppenheimer is to take in an assault of stimuli — visual, sonic, and emotional. Nolan’s bombastic style is at a pinnacle, grabbing you immediately by the ear lobes, shoving your face into its IMAX screen and prying apart your eyelids. As the flames rip apart the background, you are greeted with this comforting message:

“PROMETHEUS STOLE FIRE FROM THE GODS AND GAVE IT TO MAN.

– Nolan, Bird, Sherwin, Me, Aeschylus, et al.

FOR THIS, HE WAS CHAINED TO A ROCK AND TORTURED FOR ETERNITY.”

In Batman Begins, Nolan directs, amongst a slew of other stars, a young Cillian Murphy to the role of the Scarecrow, a seemingly respected psychiatrist who’s obsessed with the power Fear has over the human condition. The good doctor is so enthralled with his studies that he creates a toxin that makes men see their deepest fears realized in their mind’s eye, hoping to unleash humanity’s potential.

(I’m hoping at this point the primer was worth it.)

In their latest reunion, Murphy takes on the eponymous role; one that will likely define him, were he to allow it. His performance sweeps across Oppenheimer’s life – From a sweating, neophyte harkening genius; synapses snapping with visions of Monet and the cosmos, to a feeble, reserved, and defeated honoree. For as marble-mouthed and jerking as TENET seemed to be, Oppenheimer is explicit: there is a man out of sync with the present day and he will take us with him, whether we are ready or not.

Oppenheimer the student, the professor, the director and the man is constantly warning those around him that they are bounds behind not only him, but reality. While in Europe, he grows frustrated with lab work and wants to practice theory. When he becomes a renowned theorist, he is worried that no one is teaching Americans about the new radical sciences and sets off to Caltech. When he’s too busy debating about the Popular Front or the role of unionizing the physics department he helped establish at Berkeley, the Germans beat him and his colleagues to the splitting of the atom — something he and his crafted theory thought impossible. Finally, once he has science on his side, he helps beat the drum of warning to Uncle Sam that the Nazis were a year ahead of us in trying to blow up the whole world. This is where the American myth and J. Robert Oppenheimer intersect, fatally.

While the crux of the film takes place, rightfully, in Los Alamos, the heart and soul of the movie jet between Washington, D.C. and Berkeley, California. Berkeley, sitting whimsically on the left side and shoulder of Oppenheimer and D.C. grinding away and breathing heavily on his right. The two times Oppenheimer is laid bare before the audience are at these coastal polarities. Once in a post-(or inter-)coital philosophical debate in a hotel room in San Fransisco with his soon-to-be doomed lover, and once in a bureaucratic hearing in a room in D.C., awaiting a decision on his soon-to-be doomed career. It seemed, whichever shoulder he were to lean on were to lead him to disaster — and somehow even that impossible balance lead him to help create The Bomb.

There are the obvious moral questions — Nolan nor Oppenheimer shy away from the fact that this is perhaps the major ethical dilemma of our times. On one hand, you’re making a thing that will likely kill thousands, maybe even everyone… on the other hand, so are the Nazis. As such, it’s easy to conclude what those on the Manhattan Project realized — this was important and just. But when the Nazis fall, the tests and work continue. Voices raise. D.C. is calling. Oppenheimer has a decision to push us forward or pull us back into the world we currently reside.

It’s that gambit in which Oppenheimer encircles himself. He is a man of endless optimism. Hope does not yet sit trapped in a capsule on a shelf in a story in his mind. He vividly peers into the beginnings and the ends of all things at once and within them their endless possibilities and combinations. He sees, clearly, the ability for humanity to make a choice to end war and scarcity, sitting on a chalkboard before him. Next to it, he sees the world, engulfed in flames. Does he open the capsule? Does he let the world peer inside?

A choice is an odd thing in myth. If a God or a Titan or even a pretty sly looking Man comes to you with two options and both seem equally good (or equally bad) — ask what’s behind door number three. If they are fair, everyone may get out alive.

We know the choice Oppenheimer and humanity make in the main story, for better or worse. At somewhere around the 90-minute mark, one of cinema’s most breathtaking sequences begins to build a peak of aural madness and physical discomfort. Nolan employs the masterful Ludwig Göransson and Richard King and allow them to build an acoustic landscape that will fill the blank space between your cells and jolt your being. When the Los Alamos portion of the film concludes roughly 30 minutes later in a little gymnasium in New Mexico, I’d be surprised if you – like me – weren’t gripping your armrests, wishing you were somewhere else.

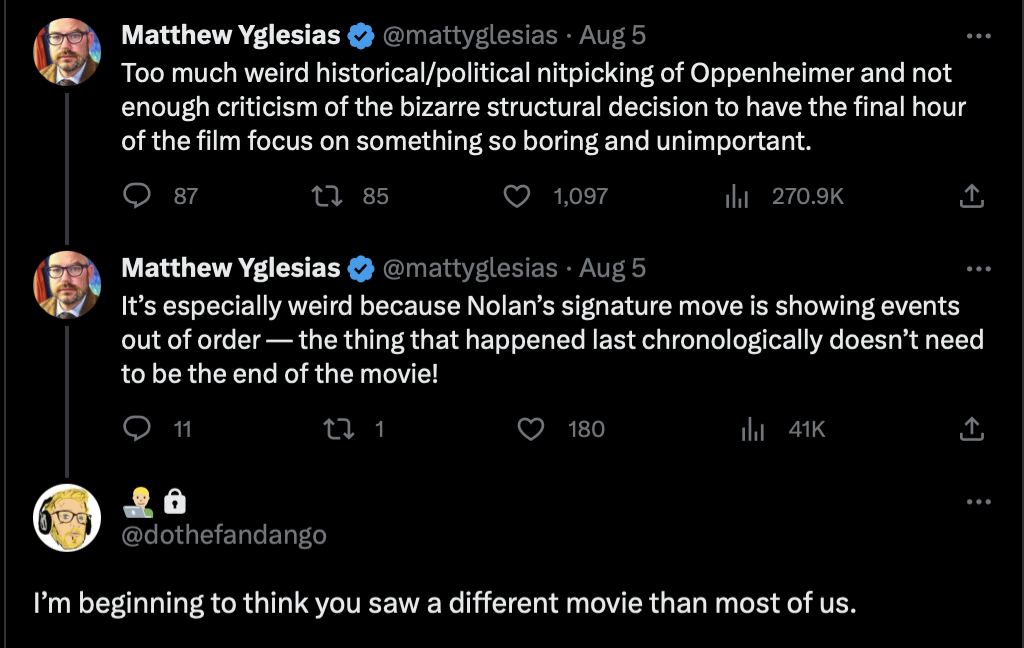

From this point forward in the film is where the few critics of Oppenheimer start to whinge. Just as the first act largely took place in Oppenheimer’s origins in California, and the second during his heroic journey in the sands of New Mexico, his return home — to his creator — is in the District of Columbia. It is there we see Oppenheimer chained to the rock of American politics, heart pecked out repeated for all to see. He tried to write a new mythology for America, but its arc strayed too far from the ones someone else had already written down before him — a man named McCarthy, who fashioned himself a Titan, was willing to use Fear to push us towards a new American era.

Comparative to bomb-building, it is perhaps less compelling. I’ve read calls that Nolan shied away from the true horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, making the characters absorb the vulgarity for us instead. It’s a decision, I think is wise for reasons not worth exhausting here. A few popular journalists (as if that means anything) were perturbed at the pace of the final act, as if the balance of a man’s character is not determined by his wake, but the size of the explosion he creates when he arrives.

To me, it’s in this ultimate portion that Oppenheimer shines. Robert Downey Jr.’s deft portrayal of American Politician Lewis Strauss attempts to steal the show, and Strauss attempts to mythologize all the evils he aided in escaping right back into The Bomb. The ancillary character in Oppenheimer, Strauss always found himself on the edge of modernity, a glass buffer between the Great Minds and where he sat. Nolan cleverly bookends the film with interactions between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, Trustee Strauss out of earshot in the distance. Strauss, after years of politicking had clawed his way up to a Commission somehow in charge of Atoms. Whether anything he did there, or Princeton, is the subject of a myth in and of itself.

Rebounding between committee investigations, the film’s finale shows us Strauss’s attempt at writing that myth into the annals of Congress (and his own petition to God) as Secretary of Commerce. He implores the Chorus to sing for him as the Titans of Earth judge him worthy of entry to their realm; all the while, Downey Jr.’s perfectly jutting jaw is captured in pristine, austere grayscale. Meanwhile, Oppenheimer sweats in a windowless backroom of an anonymous office, the tepid blues of the sweat drops on his forehead keenly captured. There he sits, hovered over by lawyers having his own history twisted into the story of a traitor and scoundrel and entered into the record; admissible in a court of law. The viewer is ping-ponged between decades and consciousnesses, philosophies and pasts — asked to consider who, if anyone, was doing what was truly right? To this, Oppenheimer offers Strauss his withering body and bones as a sacrifice, wrapped in the glistening fat of the Commerce Secretary job, hoping, correctly, that he chokes on them.

If no stone were left unturned, Politicians like Strauss and McCarthy may have had the final say in Oppenheimer’s myth. Bird, Sherwin, Nolan, Murray, and countless others strove to make sure this was not the case. And after three hours, the final warning let out by Oppenheimer thrusts you right back to where you started, in a rhapsody of fire — mind consumed what has been unleashed on man.

The final message of Oppenheimer to the audience can evoke Fear, but I instead choose to leave you with this, which I think better encapsulates what the ending means to me. We have to hope that the mechanisms that allow for new systems of change, that fire that Prometheus gave us as humans, will find that universe that Oppenheimer saw so vividly and sought to create: without war, without suffering, and without Fear.