0: Introduction

“The world was to me a secret which I desired to divine.”

— Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

In the summer prior to 10th grade, I was assigned to read the entirety of The Tale of Two Cities and Frankenstein by one of the best teachers whom I ever had the pleasure of learning from. The task was torture for a 14-year-old, but the works formed an impression on me that lasts two decades later. The concept was simple: humans largely aren’t ready to deal with their own futures, even in the past. I have long since adopted a play on the subtitle to Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus as my own tongue-in-cheek subtitle to most of my ramblings, calling myself the post-modern prometheus.

In 2023, as we hurdle towards another “new” modernity, we are allowed to receive two more colossal works: Barbie and Oppenheimer. They are works we should struggle with, as adults, in the same way I completely melted down to my parents (likely a handful of times) in the summer of 2004. They both make us look at the choices we allowed ourselves to make, in the name and idea of Americanism. They are a pondering if what we have done, and are doing, is still sane and what exactly happens when we begin to disregard all we have come to know.

1: Prometheus

Zeus and humanity had a weird relationship that I still don’t really get, but we talked about it a lot in late-20th / early-21st century American Public Schooling, so forgive me if I’m light on details but heavy on sarcasm. Mythology belongs to the teller, so take a seat.

As it goes, a Titan by the name of Prometheus tricked Zeus into eating a bunch of bones and as a punishment took away fire from man. Well, tricked is one view at it — and a fascist one at that. Zeus asked for an offering, so Prometheus lay before him two choices: filet wrapped in ox stomach, or bones wrapped in fat and tallow. Zeus, not wishing to inspect closely, picked the latter. Prometheus gave Zeus’s rejected choice, the nutritious and delicious filet, to mortal men, whom he liked better anyhow.

Zeus, by most accounts, craved order and fealty. Pride was the trait he found himself wrinkling his nose at most. Just ask Ixion, who tried to seduce his wife — he’s spending eternity on a rotisserie in Hades. Prometheus knew this and showed it in Zeus’s face. To punish Prometheus, Zeus withheld the power of fire from mortal men. Fire allowed man to create and cultivate without the aid of immortals (as this generally displeases Gods). But, this punishment also made Prometheus pretty miffed; he kinda liked those ambitious, weird, mortal men, dumb and cold and squishy as they were.

The details are scant, but in his enigmatic ways Prometheus whisked a flame from Olympus via a fennel stock and bestowed it upon mankind. From there, they forged civilization along with arts and sciences — and this really displeases type-A Zeus. And so, he sentenced Prometheus to a lifetime of eternal damnation of being chained to a rock, his liver pecked out by a bird of prey each day; regrown each night. Even Hephaestus, the God of Fire and Forgery, thought it a little radical.

I am not bold enough to use sheer force

PROMETHEUS BOUND [20 / 15], AESCHYLUS (trans. Ian Johnston)

against a kindred god and nail him down

here on this freezing rock. But nonetheless,

I must steel myself to finish off our work,

for it is dangerous to disregard

the words of Father Zeus.

Perhaps that’s why Prometheus stuck out to me (and to Shelley) so much — despite the others that so earnestly sought to mock or challenge Zeus, Prometheus showed Zeus the error in Zeus’s own hubris by allowing him to choose what seemed good over what could be found to be good. And to allow humanity to suffer from Zeus’s own error, that seemed a bridge too far. So, Prometheus gifted mankind with the ability to harness energy and change life as we know it, and that really pissed off the higher ups. And that was supposed to motivate the public to obey, fear, and worship Zeus? I would be fiercely on the side that granted me the power to make bread and smoked meats — Team Titan. Which is precisely why Zeus came up with his most ingenious punishment yet.

2: Pandora

If there were mortal women in Greek mythology before Pandora, their stories were not well-recorded. When Zeus grew tired of torturing Prometheus over his bestowal to man, he and his fellow Olympians crafted Pandora from clay. She was a nearly perfect being with blinding beauty, ceaseless curiosity, and — in true Grecian fashion — an ominous offering. Pandora wasn’t destined to land amongst mere mortals, that is — she was hand-delivered to Epimetheus, Prometheus’s brother who lived amongst the mortals.

Prometheus and Epimetheus admired the mortals, but Prometheus was more radical than his brother. Epimetheus was kind and cared for man, but his love for them was simple comparative to Prometheus; humans were but one of the many mortal animals he had grown to admire on Earth. Prometheus often warned his brother that Zeus had it out for them and these men in particular, but Epimetheus found himself tuning out amongst the hares and the bulls. So when Zeus presented the first mortal woman to Epimetheus, he did what we all do: he gawked and introduced himself.

But Epimetheus’s fatal mistake was that he also did what we all do the first time we meet a beautiful woman: he ignored what accessories she had with her. Just before she was to make his acquaintance, Zeus slipped Pandora a betrothal gift, of sorts. A beautiful, adorned capsule; never to be opened. Epimetheus could have known this, if he asked Pandora what she had in her hand. Epimetheus could have known that something was probably up if he ever wondered what was on Pandora’s mind. Epimetheus did neither of these things, not necessarily because he was a Titan or necessarily because he was a man, but probably because of a little of both. And so, Pandora grows bored and stares.

What could possibly be inside a thing that shouldn’t be opened?

What could possibly offend a Titan?

Why did she have to have it?

So Pandora does what any of us would have done, and opens the darn thing.

Almost instantly, a deep, guttural cold embraces her. The flora are bleached of their colors and her legs seem to fail her. She hears in the distance grown men start to weep, as their crops and houses begin to wilt and crumble. She musters just enough strength to pull herself towards the capsule, each inch darker and icier than the last. Finally, she manages to pry it shut, with a small rattle remaining inside of it, itching to get out. The cries stop, momentarily, but the knowledge of how quickly it will all soon fade away never seems to leave.

Epimetheus returns too late, seeing all of man and Pandora, trembling with fear. Knowing just like his brother’s actions progressing humanity cannot be undone, neither can his dooming it and so he destines himself to live amongst the men. Every day he returns home to Pandora, as beautiful as ever, hopelessly staring at the box — wondering what she left inside.

3: Hope

Myths are public dreams, dreams are private myths.

– Joseph Campbell

What we talk about when we talk about hope changes from person to person, thought to thought, reality to reality. The unique part of the American mythos is that we are often oblivious to what Pandora supposedly left trapped inside her jar. We, sometimes uniquely, sometimes frustratingly, rely on the idea that Hope alone is enough to persevere.

But there was likely a reason that hope remain encapsulated to the Ancient Greeks. Not that humanity could never attain it, for if that was the case I do not think Prometheus would have done what he had done to progress man. You do not accidentally combine fire and ore and make steel — you hope the next thing you do makes a stronger sword. It’s more likely, to me, that Hope, if undiluted, is as powerful a poison as anger, blame, or fear itself. Letting just a little bit of Hope out was just the right anxiety cocktail to keep humanity moving forward, wondering what was waiting for them around the next corner.

One aspect of our American delusion stems from the fact that a significant portion of our origin story is written down. While each culture has their own scribbled somewhere, most were not contemporaneously written — some details may have been lost in communication and therefore not admissible in a court of law. And even fewer were written down, signed and then sent to a King as a matter of record. These authors studied and knew all the stories of God divining Men to domain over land and people. To make their story unique, they knew they must petition God himself — just this time via King George III.

If those scrappy, history nerds could repel the God’s greatest Navy and battalions, was there anything that couldn’t be wrestled and arraigned to their desire? By pen and by power, men took the land and its resources, writing rule after rule that favored themselves over the other, allowing whoever wrote the friendliest letter with the most padding in the envelope take what they wanted and leave the rest for the future to figure out. They bent the Judeo-Christian good word to their will and proudly proclaimed: “God only helps those who help themselves.” They left out the part about the gold and gunpowder on purpose, I suppose. The unique blend of Hope mixed with that blind Faith that piety so deftly requires is the true blend of myth that we Americans so truly get high upon.

The modern American mythologist is the Politician. Once the land had been allocated and turned over a few times, empire was no longer the goal of the people (though the Titans that still rumbled amongst us had yet to squelch their thirst, and likely never will). As such, the Politician must sell the people on their origin story, heroic arc and fatal flaw. They must tell them the myth of the future America, one where their problems are solved and that hope that seems so locked away in a capsule that they can’t see, it’s there. They know because they’ve tasted it, and they want you to taste it too; if you’d just grant them a teensy bit of power first. And that’s where our myths cross into modernity — eventually the story they peddle gets bought and produced, the world’s largest military might and capital machine becomes a theatre stage, again and again.

4: “Oppenheimer”

Spoiler Alert. You’ve been warned.

And now things are already being transformed

PROMETHEUS BOUND [1329 / 1080], Aeschylus (trans. Ian Johnston)

from words to deeds—the earth is shuddering,

the roaring thunder from beneath the sea

is rumbling past me, while bolts of lightning

flash their twisting fire, whirlwinds toss the dust,

and blasting winds rush out to launch a war

of howling storms, one against another.

The sky is now confounded with the sea.

This turmoil is quite clearly aimed at me

and comes from Zeus to make me feel afraid.

O sacred mother Earth and heavenly Sky,

who rolls around the light that all things share,

you see these unjust wrongs I must endure!

Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin did the hard work for me in parallelizing myth and Oppenheimer in American Prometheus, just around the time Christopher Nolan was debuting an origin story of his own: Batman Begins.

To experience Oppenheimer is to take in an assault of stimuli — visual, sonic, and emotional. Nolan’s bombastic style is at a pinnacle, grabbing you immediately by the ear lobes, shoving your face into its IMAX screen and prying apart your eyelids. As the flames rip apart the background, you are greeted with this comforting message:

“PROMETHEUS STOLE FIRE FROM THE GODS AND GAVE IT TO MAN.

– Nolan, Bird, Sherwin, Me, Aeschylus, et al.

FOR THIS, HE WAS CHAINED TO A ROCK AND TORTURED FOR ETERNITY.”

In Batman Begins, Nolan directs, amongst a slew of other stars, a young Cillian Murphy to the role of the Scarecrow, a seemingly respected psychiatrist who’s obsessed with the power Fear has over the human condition. The good doctor is so enthralled with his studies that he creates a toxin that makes men see their deepest fears realized in their mind’s eye, hoping to unleash humanity’s potential.

(I’m hoping at this point the primer was worth it.)

In their latest reunion, Murphy takes on the eponymous role; one that will likely define him, were he to allow it. His performance sweeps across Oppenheimer’s life – From a sweating, neophyte harkening genius; synapses snapping with visions of Monet and the cosmos, to a feeble, reserved, and defeated honoree. For as marble-mouthed and jerking as TENET seemed to be, Oppenheimer is explicit: there is a man out of sync with the present day and he will take us with him, whether we are ready or not.

Oppenheimer the student, the professor, the director and the man is constantly warning those around him that they are bounds behind not only him, but reality. While in Europe, he grows frustrated with lab work and wants to practice theory. When he becomes a renowned theorist, he is worried that no one is teaching Americans about the new radical sciences and sets off to Caltech. When he’s too busy debating about the Popular Front or the role of unionizing the physics department he helped establish at Berkeley, the Germans beat him and his colleagues to the splitting of the atom — something he and his crafted theory thought impossible. Finally, once he has science on his side, he helps beat the drum of warning to Uncle Sam that the Nazis were a year ahead of us in trying to blow up the whole world. This is where the American myth and J. Robert Oppenheimer intersect, fatally.

While the crux of the film takes place, rightfully, in Los Alamos, the heart and soul of the movie jet between Washington, D.C. and Berkeley, California. Berkeley, sitting whimsically on the left side and shoulder of Oppenheimer and D.C. grinding away and breathing heavily on his right. The two times Oppenheimer is laid bare before the audience are at these coastal polarities. Once in a post-(or inter-)coital philosophical debate in a hotel room in San Fransisco with his soon-to-be doomed lover, and once in a bureaucratic hearing in a room in D.C., awaiting a decision on his soon-to-be doomed career. It seemed, whichever shoulder he were to lean on were to lead him to disaster — and somehow even that impossible balance lead him to help create The Bomb.

There are the obvious moral questions — Nolan nor Oppenheimer shy away from the fact that this is perhaps the major ethical dilemma of our times. On one hand, you’re making a thing that will likely kill thousands, maybe even everyone… on the other hand, so are the Nazis. As such, it’s easy to conclude what those on the Manhattan Project realized — this was important and just. But when the Nazis fall, the tests and work continue. Voices raise. D.C. is calling. Oppenheimer has a decision to push us forward or pull us back into the world we currently reside.

It’s that gambit in which Oppenheimer encircles himself. He is a man of endless optimism. Hope does not yet sit trapped in a capsule on a shelf in a story in his mind. He vividly peers into the beginnings and the ends of all things at once and within them their endless possibilities and combinations. He sees, clearly, the ability for humanity to make a choice to end war and scarcity, sitting on a chalkboard before him. Next to it, he sees the world, engulfed in flames. Does he open the capsule? Does he let the world peer inside?

A choice is an odd thing in myth. If a God or a Titan or even a pretty sly looking Man comes to you with two options and both seem equally good (or equally bad) — ask what’s behind door number three. If they are fair, everyone may get out alive.

We know the choice Oppenheimer and humanity make in the main story, for better or worse. At somewhere around the 90-minute mark, one of cinema’s most breathtaking sequences begins to build a peak of aural madness and physical discomfort. Nolan employs the masterful Ludwig Göransson and Richard King and allow them to build an acoustic landscape that will fill the blank space between your cells and jolt your being. When the Los Alamos portion of the film concludes roughly 30 minutes later in a little gymnasium in New Mexico, I’d be surprised if you – like me – weren’t gripping your armrests, wishing you were somewhere else.

From this point forward in the film is where the few critics of Oppenheimer start to whinge. Just as the first act largely took place in Oppenheimer’s origins in California, and the second during his heroic journey in the sands of New Mexico, his return home — to his creator — is in the District of Columbia. It is there we see Oppenheimer chained to the rock of American politics, heart pecked out repeated for all to see. He tried to write a new mythology for America, but its arc strayed too far from the ones someone else had already written down before him — a man named McCarthy, who fashioned himself a Titan, was willing to use Fear to push us towards a new American era.

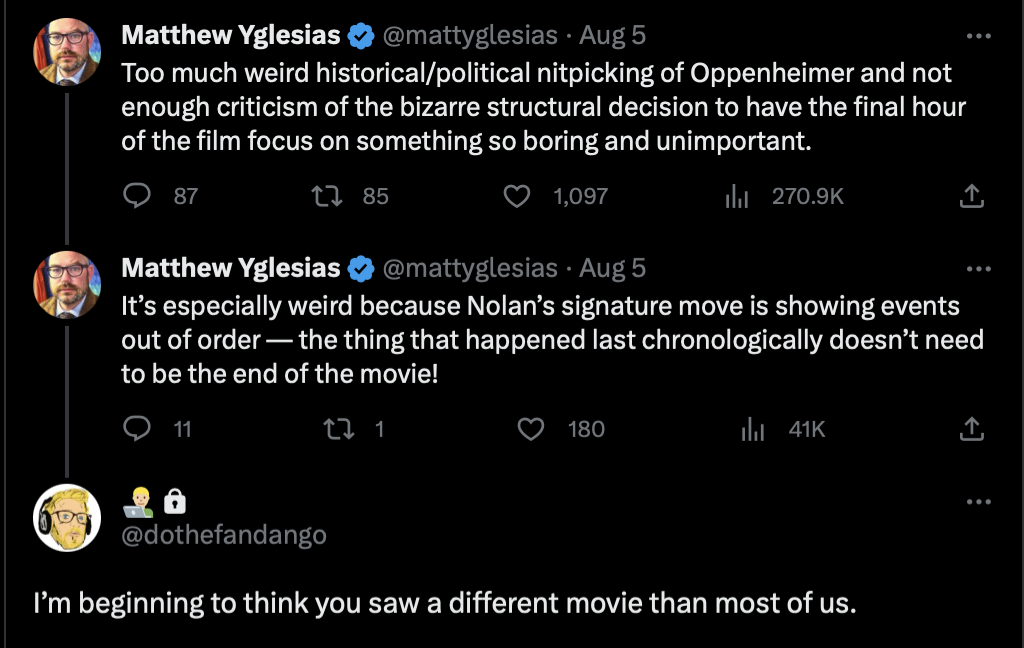

Comparative to bomb-building, it is perhaps less compelling. I’ve read calls that Nolan shied away from the true horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, making the characters absorb the vulgarity for us instead. It’s a decision I think is wise for reasons not worth exhausting here. A few popular journalists (as if that means anything) were perturbed at the pace of the final act, as if the balance of a man’s character is not determined by his wake, but the size of the explosion he creates when he arrives.

To me, it’s in this ultimate portion that Oppenheimer shines. Robert Downey Jr.’s deft portrayal of American Politician Lewis Strauss attempts to steal the show, and Strauss attempts to mythologize all the evils he aided in escaping right back into The Bomb. The ancillary character in Oppenheimer, Strauss always found himself on the edge of modernity, a glass buffer between the Great Minds and where he sat. Nolan cleverly bookends the film with interactions between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, Trustee Strauss out of earshot in the distance. Strauss, after years of politicking had clawed his way up to a Commission somehow in charge of Atoms. Whether anything he did there, or Princeton, is the subject of a myth in and of itself.

Rebounding between committee investigations, the film’s finale shows us Strauss’s attempt at writing that myth into the annals of Congress (and his own petition to God) as Secretary of Commerce. He implores the Chorus to sing for him as the Titans of Earth judge him worthy of entry to their realm; all the while, Downey Jr.’s perfectly jutting jaw is captured in pristine, austere grayscale. Meanwhile, Oppenheimer sweats in a windowless backroom of an anonymous office, the tepid blues of the sweat drops on his forehead keenly captured. There he sits, hovered over by lawyers having his own history twisted into the story of a traitor and scoundrel and entered into the record; admissible in a court of law. The viewer is ping-ponged between decades and consciousnesses, philosophies and pasts — asked to consider who, if anyone, was doing what was truly right? To this, Oppenheimer offers Strauss his withering body and bones as a sacrifice, wrapped in the glistening fat of the Commerce Secretary job hoping, correctly, that he chokes on them.

If no stone were left unturned, Politicians like Strauss and McCarthy may have had the final say in Oppenheimer’s myth. Bird, Sherwin, Nolan, Murray, and countless others strove to make sure this was not the case. And after three hours, the final warning let out by Oppenheimer thrusts you right back to where you started, in a rhapsody of fire — mind consumed what has been unleashed on man.

The final message of Oppenheimer to the audience can evoke Fear, but I instead choose to leave you with this, which I think better encapsulates what the ending means to me. We have to hope that the mechanisms that allow for new systems of change, that fire that Prometheus gave us as humans, will find that universe that Oppenheimer saw so vividly and sought to create: without war, without suffering, and without Fear.